Eqbal Ahmad 25 Years On: Personal and Political Legacies - New York, Thursday May 23rd 2024 - Video - 1

May 2024 marks 25 years since the death of Eqbal Ahmad on May 11, 1999. Eqbal's family, friends, fans, and broader community gathered in New York on Thursday May 23rd 2024 to commemorate his lasting influence on all of us, as well as the continuing relevance of his thoughts, writings, and actions on Palestine, South Asia, North Africa, Vietnam, and global anti-imperial struggles more broadly. Speakers include Lila Abu-Lughod, Dohra Ahmad, Zuli Ahmad, Kamran Asdar Ali, Siraj Ali, Julie Diamond, Ayesha Le Breton, Zia Mian, Kavita Ramdas, Robin Varghese and Margaret Cerullo.

Hosted by Eqbal’s family and The Eqbal Ahmad Project

Watch the Event at the Link - Eqbal Ahmad 25 Years On: Personal and Political Legacies - New York, Thursday May 23rd 2024 Video

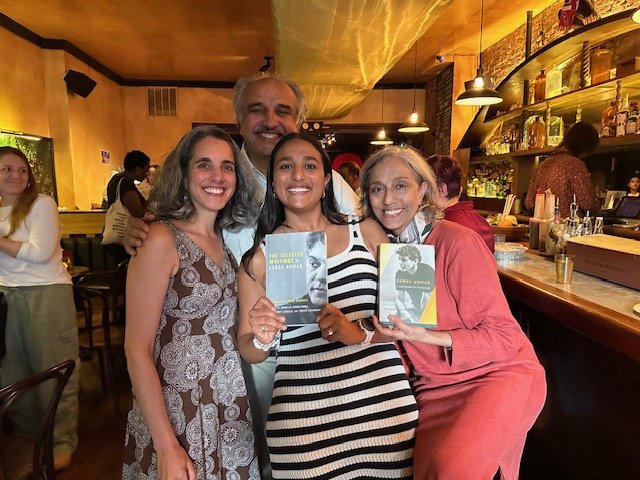

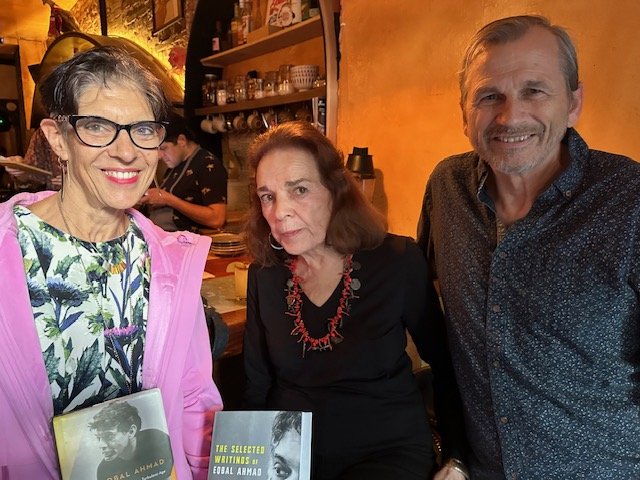

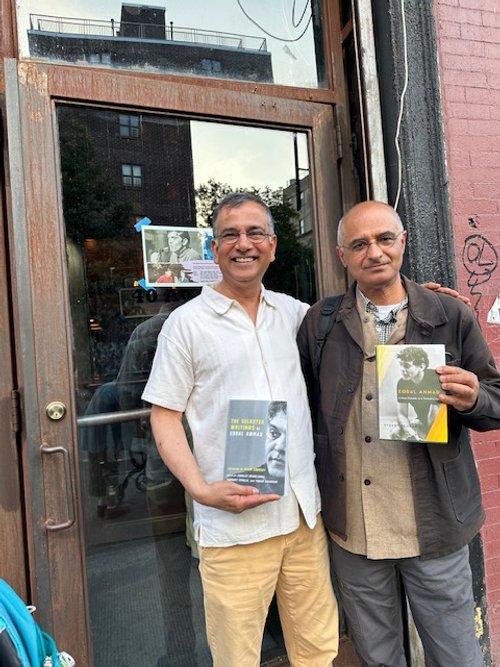

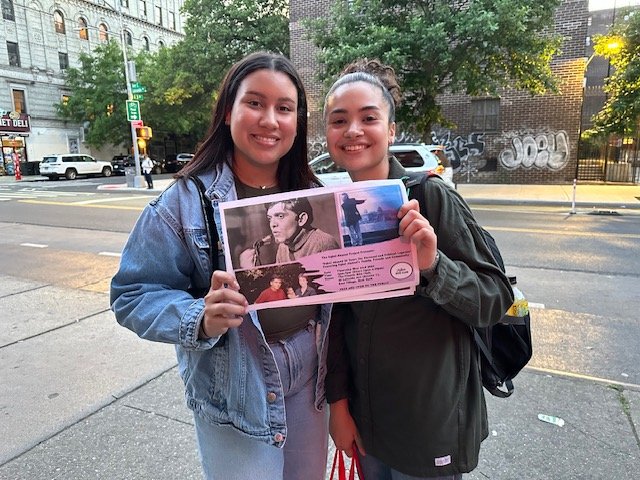

In the next sections below you can read the tribute wall consisting of messages from Eqbal Ahmad’s friends and colleagues, written especially for the New York community event. Plus we feature event images for you.

Anthony Barnett, Transnational Institute

When I look back now at meeting Eqbal in Holland at the start of the TNI in the seventies I suddenly realise that he was — in an extraordinary way — a visitor from the future. I had no way of knowing this at the time.

In his company I recall how he was apparently deeply tired with the world – including us in the Institute - while unwaveringly committed to it and the fight for change. In the fifty years since then, the pitiless, churning violence of the neoliberal order has generated many like Eqbal. Not his equal perhaps because there were none before him. But like him: unable to live safely in their own country, fluent in different languages (in a way that I am not), radically opposed to the existing world yet genuinely cosmopolitan. Restless and tired of restlessness. Rooted in humanity and eloquently taking a delight in it.

Let no one ever say there was not an alternative to the way we have been ruled. There always was. Those like Eqbal were the proof.

Carollee Bengelsdorf, Hampshire College

Eqbal first came to lecture at Hampshire College in 1976. Classes with small groups of students soon escalated into mass gatherings of students, faculty and staff. Classes which were to last 1 and 1/2 hours went on for a minimum of three hours, with no one making the least move to leave. The only person who seemed somewhat impatient was Eqbal's then six year old daughter Dohra who leaned over to one of us and whispered: "Is Poppy almost finished? Because it's very boring.” Some years later, Eqbal was appointed Professor at the College to the great good fortune of all of us on campus and in the community as a whole. Eqbal was, of course, a brilliant and much adored teacher and a charismatic speaker but his charisma was rooted in something more, something deeper. He was that rare human being who was comfortable in his own skin, something he achieved despite the tragedies through which he had lived. He was a truly gentle soul contained within a fierce desire for justice and a correspondingly fierce need to battle for it in multiple ways and on multiple fronts. And yet he was an infinitely patient man: he knew speaking truth to unjust regimes involved both short and long term strategies and it involved organizing people at the base: he learned this from his experiences with the Algerian and Vietnamese wars of liberation.

Eqbal could speak to and with anyone at any age. He was sought out by journalists, academics, political leaders, and by young people involved in various forms of liberation struggles in the United States, in Asia and elsewhere, all of whom drew upon his sharp analytical mind rooted in a solid grasp of the arc of history and histories, a love of language and of poetry. Perhaps this is in part the reason why a horde of international and national leftists as well as local organizers and students descended upon Hampshire to celebrate him when he retired from the College. Amidst the festivities, his closest friend Edward Said, who cried when he spoke of what Eqbal meant for the Palestinian nation, insisted that Eqbal do something to bring together the thousands and thousands of pages of writings, written at moments into immediate situations all over the world and published in multiple forms in an infinite variety of newspapers and journals, as well as lengthy in-depth analyses published as well in diverse media, so that they not be lost to the generations to come who would need them. We knew Eqbal was not likely to do this so three of us formed what we called Eqbal's senior thesis committee and began the task of gathering and culling through this disparate body or better said bodies of work in an effort to situate them in a fashion that would elucidate their historical import and their currency. It took us a while. Eqbal died before the book had been put together, as did Edward Said, who was to write the introduction. Noam Chomsky then took on the writing of this introduction. In the process of gathering the material for "The Selected Writings of Eqbal Ahmad" published by Columbia University Press and in Pakistan by Oxford University Press, we established an archive of Eqbal's work, housed in the Hampshire College library.

One final personal note: Eqbal picked me up when I was nineteen years old, hitchhiking at Cornell University where I was a student and he was a professor. It was certainly the best "pickup" of my life. From that point on I became a member of the extended Eqbal family, gathered perched on rugs in the apartment he shared with Julie and Dohra in New York, or feasting endlessly upon the Pakistani/ Indian menu he produced for any given occasion, or again sitting on rugs while he examined and bargained for one he would spot in a pile, or going to auctions where he would take such delights in his 'finds.' To say nothing of getting to hear him give talks and attending seminars and panel discussions on which he was a member. Eqbal was the blessing of many people's lives. He was the blessing of mine.

Remembering Eqbal……

Yogesh Chandrani

May 23, 2024

It has been twenty-five years since Eqbal left us, and I still find it difficult to describe the grief and the loss that I have felt since 1999. Although I continue to find myself at a loss for words, it is Eqbal’s words that have sustained me in these dark times as I am sure they have sustained everyone who is gathered here today. A part of me is glad that Eqbal did not live to see the attacks of 9/11 and a world remade by America’s endless wars of revenge. Soon after 9/11, I remember sharing Eqbal’s writings with friends at Columbia. Although many of them had heard of him, they had never read him. Several amongst these friends described his work as invaluable in making sense of the 9/11 attacks and their violent, racist legacies in the United States and South Asia; a few were even inspired by Eqbal’s work to write pathbreaking works on the war on terror.

As we bear witness to Israel’s genocidal war on the Palestinian peoples, Eqbal’s essays on the Middle East, beginning with his Pioneering in the Nuclear Age and his later essays comparing Israel’s occupation of Palestinian lands with apartheid South Africa, continue to be our companions in making sense of the latest chapter in the nakba. Israel’s assault has precipitated protests on numerous college campuses including at Colorado College, where I teach. My students have organized remarkable and creative protests calling for a ceasefire and for an end to American sponsorship of the genocide. Jewish students have come together with Arab, Muslim, Black, indigenous, and white students to demand that their political leaders and the older generation end their unconditional support for Israel’s systematic assault on Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank. As I support them, it is Eqbal’s words, and above all his uncompromising integrity and moral clarity, that have continuously sustained me.

Since October 7, I have wondered about what Eqbal would have been doing at this moment. While he would have condemned the Hamas organized attack of October 7th, I can imagine him travelling to campuses all over the US and beyond, visiting encampments and speaking with a moral clarity that is so lacking in our public sphere. In a mediascape dominated by genocidaires and by experts hiding their bigotry behind facile claims that Israel has a right to defend itself or that history began on October 7th, he would have reminded his American audiences that the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians is not complicated, and that history did not begin on October 7. Rather, in his inimitable style, he would have pointed out that the language of our elites obscures what is at its core a conflict between the settler colonial project of Israel and the Palestinian longing for a life of dignity and freedom. I can imagine him reiterating the argument that he made in “Pioneering in the Nuclear Age,” that Israel’s settler colonialism was driven by an eliminationist logic backed by the unconditional support of the United States, the most powerful settler colony in recorded history. I can imagine him reminding his audiences that the Palestinian peoples had tried to resist nonviolently during the first intifada and again in 2018 in the form of the great march of return. In both instances, their struggles for a life of dignity and freedom and their right to return home had been met with Israeli violence and undermined by a combination of corrupt leaders and America’s unconditional support for Israel. He would have argued as he did well before most scholars were willing to dare—that the Israeli state was like any other settler colonial state, its actions driven by an eliminationist logic. What was distinctive about it, he would have argued, is the unconditional support of the United States for Israel’s eliminationist project; a support that is based on the legitimacy of Zionism in American political culture and of America’s investment in empire.

When the first intifada began in 1987, I was his student at Hampshire College and had just finished Eqbal’s class on revolutionary warfare. For many of us, it was our introduction to the wars of liberation in Algeria, Vietnam, Cuba, and Palestine. I have vivid memories of Eqbal’s lectures; his refusal to romanticize the violence of anticolonial struggles and his emphasis on the centrality of the political and of the ethical in anticolonial revolutionary struggles. Revolutionary movements, he reminded us, could only succeed if they were attuned to the political aspirations of the people they claimed to represent and only if they could offer an alternative, democratic political, cultural, and social vision. I also remember how energized he was by the young Palestinian women, men, and children; by their courage, their creativity, and their resilience in the face of Israeli violence during the first intifada. One of my most vivid memories of this time was when some of us went to see Eqbal to talk about organizing a teach-in. We were near the end of the Spring semester and what began as a tentative discussion about a teach-in soon became a more ambitious plan for a semester-long series of events on the question of Palestine that students would organize for the Fall of 1987. Eqbal helped us identify speakers to invite and ideas to raise the funds for the symposium. While he encouraged us and supported us, what I remember is his insistence that we include speakers representing the Zionist perspective because on his view, Palestinians and Jews were “two communities of suffering” and resolution of the conflict would be impossible without the each recognizing the suffering of the other. In spite of our best efforts, none of the speakers we contacted over the summer accepted our invitation. That year, Eqbal had returned to campus a couple of weeks before the semester began and a group of us went to see him in a panic. Eqbal smiled and reassured us to not worry about the speakers. He pulled up his rolodex and began to call the speakers we had invited. Within a few hours, every one of them had agreed to participate. During the symposium, several of my peers who were Jewish and had grown up in Zionist families felt deeply unsettled by some of the lectures. What I remember most vividly are the many conversations Eqbal had with them. Although he was teaching and exhausted from travelling and giving talks all over the country, he would invite students to his apartment after each lecture and spend endless hours listening to their anxieties and fears; engaging with them with a capaciousness that was remarkable. Although the students did not agree with him, I could see that they were profoundly affected by Eqbal’s generosity and his integrity.

I wanted to share these memories of Eqbal with you today because the moral clarity of his teachings on Palestine are being enacted and embodied by a new generation of students at our colleges and universities. Many of them have risked their futures; some have lost family in Gaza; others have faced the anger and rejection of family and friends or been the targets of mob and police violence. Yet, they have organized encampments, organized teach-ins, and educated themselves and their communities on the justness of the Palestinian struggle and called for an end to Israel’s genocidal war. Throughout their protests, they have been capacious and generous to each other and embodied the ideal of solidarity. Although most of these protesters were likely born after Eqbal left us and although most have probably never heard of him or read his work, in my mind, this new generation embodies his legacy and reminds me everyday of the importance of all that he lived, represented and fought for. Although I know he would be heart-broken by the unrelenting violence being endured by Palestinians today, I also know that he would be proud, inspired, and deeply moved by the expressions of solidarity and resistance against apartheid and settler colonialism that we are seeing on university campuses in the US and all over the world today.

Eqbal Ahmad 25 Years On: Personal and Political Legacies - New York, Thursday May 23rd 2024 - Tribute Wall - 2

This section consists of messages from Eqbal Ahmad’s friends and colleagues, written especially for the New York community event.

Fiona Dove, Transnational Institute

Eqbal is a legend at the Transnational Institute in Amsterdam, revered as our founding father. Few of us still within TNI actually met him, but somehow he is an enduring presence. He looks over my shoulder daily from the wall of remembrance in my office. And every newcomer is introduced to him there. Eqbal brings us many interesting visitors who come to Amsterdam to find out more about him from our archives. He even brought us the Pakistani Ambassador to the Netherlands, who was once mentored by Eqbal, and from whom we now get delicious mangos hand delivered annually. Eqbal also continues to offer wisdom relevant for now – for example, with respect to Palestine. We know Eqbal only through others’ memories and his words that have survived. Our sense of the man is that he was a prescient analyst, a spell-binding speaker, and a debonaire revolutionary whose socialist utopia was a joyful one. We are the heirs of Eqbal’s legacy, and we hope we have done him proud as we mark 50 years since he first opened our doors.

Richard Falk

It’s wonderful that you have thought of doing this legacy event 25 years after Eqbal’s death and our deep, persisting loss. In my experience Eqbal, besides being a warm, loyal, and generous friend, was as a public figure the most impressive progressive personality at combining passion, knowledge, and humane insight.

I’m thinking about four international trips that exhibited Eqbal’s wide range of concerns:

1- To Tunisia with Eqbal and Ramsey Clark to promote democracy in an event that was shut down;

2- A 1980 Meeting in Beirut with Edward Said, Eqbal, and Arafat

3- A visit to Iran in 1980 at the invitation of Banisadr, the first president of the Islamic Republic, with the lofty purpose of trying to resolve the hostage crisis at the US Embassy, included meetings with many leaders; and

4- 1998 or 1999 first ever human rights conference in Gaza at which Eqbal gave a brilliant keynote, replacing Edward who was denied a visa.

I am so glad you are doing this as among other things such a gathering is in its way a sign of resistance against the nihilism of this historical period exemplified by the reactions of the liberal democracies to the Gaza onslaught.

Adam and Arlie Hochschild

We wish we could be with all of you in New York, but instead must send you greetings from California. For both of us, knowing Eqbal for several decades was one of the most enriching experiences of our lives. A month does not pass when we don’t think of what he would make of events happening in the world or of the people passing through our lives. How he would weep now about the unspeakable carnage unfolding in Gaza. We remember the wide span of countries, issues, and people he cared about. Perhaps because his passion for justice made it hard for him to be an unquestioning citizen or resident of any nation—indeed more than one of them put him in jail —he was truly a citizen of the world.

Yet at the same time he had such zest for life beyond politics. We remember, for instance, his unexpected delight in Paul Scott’s novels about the British in India, the care with which he spiced each of his extraordinary dishes, his love for carpets, and his explanation of the word “pukka” – a term for “perfectly done”—lifting an imaginary collar to illustrate the meaning.

There are few people on earth who make you feel: knowing him or her made me a better, larger person. Eqbal was one, and we are deeply grateful to have known him.

Daniel José Older

The first time I heard Eqbal Ahmad’s name, it was said by Arundhati Roy in a Hampshire College auditorium in 2001. Speaking of the honor it was to be giving the memorial lecture in his name, she said “The most important thing about him is not that he was respected or honored but that he was so loved, and that seems like such a rare thing today.”

I was twenty-one, the second US invasion of Iraq was imminent, and the world felt like it had been turned upside down. The veil on so much had been lifted, so many truths at once were being revealed and I had no idea how to handle it. Having entered that upside-down state, also known as reality, I was starving for writers who could help me find a path through this twisted world and all the many brutal histories that surround us. This led me to Arundhati Roy, Eduardo Galeano, James Baldwin, Edward Said, and of course, Eqbal Ahmad.

I went to find out more about him after that, and I remember sitting in the library, reading his words. I remember feeling this deep sense of relief that finally, someone was talking to us, the readers, not as strangers or judges or even students, but as friends, as if we were right there beside him in the global struggle against imperialism. There is a deep sense of intimacy in all of his works, his generosity of spirit, his truthtelling.

Mr. Ahmad spoke to the world as a fellow strategist. He wanted us to get free, all of us. He wrote that victory was a matter of out-administering, out-legitimizing empire, and that this “out-administration occurs when you identify the primary contradiction of your adversary and expose that contradiction not only to yourselves...but to the world at large.” I’ve thought of these words many, many times since I first read them. They’ve been like a guiding light along a dark road, along with the wisdom of other luminaries. I’ve seen them echoing in movements over the past twenty years, but never so much as they do today, in the student encampments, in the protests for a free Palestine that have poured through cities across the world. The primary contradiction of zionism, of empire, has been exposed for all to see, and the young people are leading us into a new era. We live in heavy times, the stakes have never been higher, but we are also surrounded by hope, in part because so many have followed the lanterns left for us by the great thinkers who came before. Eqbal Ahmad’s legacy is more than a memory, it’s a light, and it’s one that remains so strong not just because he was honored and respected, but most of all, because he was so loved.

Stuart Schaar

In 1962, when I was living in Rabat and doing research for my doctoral dissertation, Eqbal visited me. He had just crossed through newly independent Algeria by car since he himself was working on his dissertation in Tunisia. He was going to do a comparison between Tunisian and Moroccan labor unions, but his inquisitive mind got him into trouble with the head of the Moroccan union. He asked so many probing questions of the labor union leaders and found out many secrets that had been carefully hidden from public view, that the head of the union became nervous and closed the elevator of the main union building in Casablanca, shutting Eqbal out of any further access to the union leadership. Later, Eqbal wrote a 70-page book chapter on North African labor unions. It is still, some 40 years later, the best study of the subject in existence. The guy was brilliant. At all times, he surprised me with his originality and perspicuity about a myriad of subjects.

Above all, he was a democrat who abhorred all dictators no matter where they were. And together we organized for human rights and wrote about transgressions wherever we found them. Boy, were we busy. It reached a point that at times I was afraid to visit Eqbal’s apartment, since I had a busy life, and every time that I showed up at his place, I got an assignment which I could not refuse to do. Together we caused a lot of good trouble.

The most fun though was being present when Edward and Miriam Said showed up at Eqbal and Julie’s apartment. The repartee was hilarious since Edward and Eqbal loved each other and relished being in each other’s company. Edward and he would horse around and make believe they were Muslim princes of old complimenting each other with flowery language befitting Mughal royalty. All present died of laughter. Then after dinner Eqbal would recite from memory, since he had an extraordinary poetic memory, Urdu poetry that matches the great poets anywhere, ranging from 19th century Ghalib to Faiz Ahmad Faiz, and then he would simultaneously translate them into English, giving his guests an opportunity to share some of the great literature about which we were completely ignorant. These were unique wonderful occasions that could not be found anywhere else.

On this anniversary of his death 25 years ago, I want to share with you that he put me on track to write a new book that I am working on now about a 1920’s and 30’s Tunisian trade union leader and major male feminist, Tahar Haddad, who also was a grass roots democrat living in an authoritarian milieu. Eqbal and I wrote an article about him, and I am expanding our work together into a major book based on Arabic sources, which will be a well-deserved tribute to my late friend.

Adele Simmons, Hampshire College

Eqbal joined the faculty at Hampshire College in 1982 and taught world politics and political science until he retired in 1997. He was deeply admired by faculty and students alike for his impressive insights into many complex challenges. Students loved taking his courses, and appreciated the time he spent with them outside of class. His writings and his classes were always interdisciplinary and he thoughtfully challenged conventional approaches to addressing the world’s crises. He was one of the most admired and popular members of the Hampshire faculty. Hampshire was very lucky to have him on their faculty for 15 years.

[END]